WOMEN’S NUTRITION : WHY IT MATTERS?

1.CH.S.ANURADHA 2.CH.SHANTHI DEVI 3.Dr.R.HARITHA

VISAKHA GOVERNMENT DEGREE COLLEGE (W), VISAKHAPATNAM

INTRODUCTION

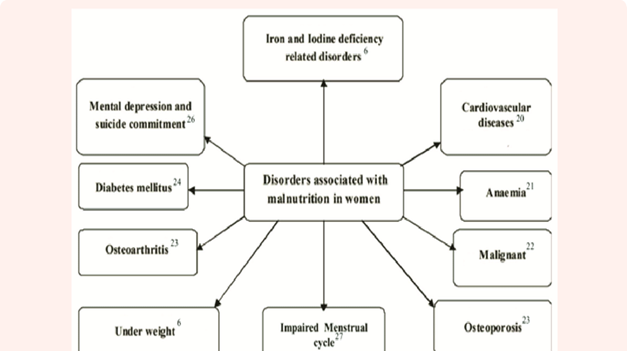

Nutrition is the process of providing or obtaining the food necessary for health and growth. The health of women is linked to their status in the society. Malnutrition poses a variety of threats to women. It weakens women’s ability to survive childbirth, makes them more susceptible to infections, and leaves them with fewer reserves to recover from illness. Malnutrition undermines women’s productivity, capacity to generate income, and ability to care for their families.

HOW NUTRITION AFFECTS WOMEN

Women are more likely to suffer from nutritional deficiencies than men are, for reasons including women’s reproductive biology, low social status, poverty, and lack of education. Sociocultural traditions and disparities in household work patterns can also increase women’s chances of being malnourished. Globally, 50 percent of all pregnant women are anaemic, and at least 120 million women in less developed countries are underweight. Research shows that being underweight hinders women’s productivity and can lead to increased rates of illness and mortality.

Many women who are underweight are also stunted, or below the median height for their age. Stunting is a known risk factor for obstetric complications such as obstructed labour and the need for skilled intervention during delivery, leading to injury or death for mothers and their newborns. It also is associated with reduced work capacity.

Adolescent girls are particularly vulnerable to malnutrition because they are growing faster than at any time after their first year of life. They need protein, iron, and other micronutrients to support the adolescent growth spurt and meet the body’s increased demand for iron during menstruation. Adolescents who become pregnant are at greater risk of various complications since they may not yet have finished growing. Pregnant adolescents who are underweight or stunted are especially likely to experience obstructed labor and other obstetric complications. There is evidence that the bodies of the still-growing adolescent mother and her baby may compete for nutrients, raising the infant’s risk of low birth weight (defined as a birth weight of less than 2,500 grams) and early death.

Iron deficiency and anaemia are the most prevalent nutritional deficiencies in the world. The body uses iron to produce haemoglobin, a protein that transports oxygen from the lungs to other tissues in the body via the blood stream, and anaemia is defined as having a haemoglobin level below a specific level (less than 12 grams of haemoglobin per decilitre of blood [g/dl] in nonpregnant women; less than 10 g/dl in pregnant women).4 Most women who develop anaemia in less developed countries are not consuming enough iron-rich foods or are eating foods that inhibit the absorption of iron. However, malaria can also cause anaemia and is responsible for much of the endemic anaemia in some areas. Other causes of anaemia include hookworm and schistosomiasis, HIV/AIDS, other micronutrient deficiencies, and genetic disorders.

Anaemia affects about 43 percent of women of reproductive age in less developed countries. Women are especially susceptible to iron deficiency and anaemia during pregnancy, and about half of all pregnant women in less developed countries are anaemic, although rates vary significantly among regions.5 Iron deficiency and anaemia cause fatigue, reduce work capacity, and make people more susceptible to infection. Severe anaemia places women at higher risk of death during delivery and the period following childbirth.6 Recent research suggests that even mild anaemia puts women at greater risk of death.7

Iodine Deficiency

Failing to meet the body’s iodine requirements impairs mental functioning and can cause goitre (a swelling of the thyroid gland) and hypothyroidism, a condition marked by fatigue and weakness. Among adolescent girls, iodine deficiency may cause mental impairments, impede physical development, and harm school performance. Although programs to iodize salt have reduced the prevalence of iodine deficiency disorders dramatically in the past 10 years, there is still wide variation in household access to iodized salt, ranging from 80 percent in Latin America to 28 percent in Central and eastern Europe. At least 130 countries have serious pockets of iodine deficiency disorders.

Vitamin A Deficiency (VAD)

VAD, which can cause growth retardation and impaired vision, remains a significant public health issue among populations that do not consume enough vitamin A, which is found in animal products and certain fruits, including mangos. Severe VAD causes blindness; less severe VAD impairs the immune system, making people more susceptible to infection and putting them at increased risk of death. Concurrent infection with parasites and illnesses such as diarrhea, as well as having several pregnancies too close together, can exacerbate VAD. Pregnant women are especially vulnerable to VAD. In Nepal, for example, where VAD is prevalent in some communities, as many as one in 10 pregnant women experience night blindness due to VAD.

HOW WOMEN’S NUTRITION AFFECTS NATIONAL ECONOMIES

Malnutrition in women leads to economic losses for families, communities, and countries because malnutrition reduces women’s ability to work and can create ripple effects that stretch through generations. Countries where malnutrition is common must deal with its immediate costs, including reduced income from malnourished citizens, and face long-term problems that may be related to low birth weight, including high rates of cardiac disease and diabetes in adults.

Illnesses associated with nutrient deficiencies have significantly reduced the productivity of women in less developed countries. It is difficult to determine exactly what proportion of those losses are due to maternal malnutrition, but recent research indicates that 60 percent of deaths of children under age 5 are associated with malnutrition — and children’s malnutrition is strongly correlated with mothers’ poor nutritional status. Problems related to anaemia, for example, including cognitive impairment in children and low productivity in adults, cost US$5 billion a year in South Asia alone. Illness associated with nutrient deficiencies have significantly reduced the productivity of women in less developed countries. A recent report from Asia shows that malnutrition reduces human productivity by 10 percent to 15 percent and gross domestic product by 5 percent to 10 percent. By improving the nutrition of adolescent girls and women, nations can reduce health care costs, increase intellectual capacity, and improve adult productivity.

POLICY OPTIONS

The Millennium Development Goals established by the UN member states in 2000 challenge nations to create effective interventions to improve women’s and adolescent girls’ nutrition. Taking such action not only improves the health of girls and women today, it has far-reaching intergenerational effects that can help countries develop.

Preventing malnutrition requires a political commitment. Public health systems need to prevent and treat micronutrient deficiencies, encourage households to meet the dietary needs of women and adolescent girls throughout their lives, and ensure their access to high-quality health services, clean water, and adequate sanitation. Policymakers should also address women’s low social status and ensure that girls have access to education — which should include information on nutrition. Such policy measures can help increase women’s age at first pregnancy, an important determinant of maternal health and child survival, and can encourage women to space their births.

CONCLUSION

Adequate nutrition is important for women not only because it helps them be productive members of society but also because of the direct effect maternal nutrition has on the health and development of the next generation. There is also increasing concern about the possibility that maternal malnutrition may contribute to the growing burden of cardiovascular and other noncommunicable diseases of adults in less developed countries. Finally, maternal malnutrition’s toll on maternal and infant survival stands in the way of countries’ work towards key global development goals.

REFERENCES

- Rae Galloway et al., “Women’s Perceptions of Iron Deficiency and Anemia Prevention and Control in Eight Developing Countries,” Social Science & Medicine55, no. 4 (2002): 529-44.

- Administrative Committee on Coordination (ACC)/Sub-Committee on Nutrition (SCN) and International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Fourth Report on the World Nutrition Situation(Geneva: ACC/SCN, 2000); and Commission on the Nutrition Challenges of the 21st Century, Ending Malnutrition by 2020: An Agenda for Change in the Millennium (February 2000), accessed online at http://acc.unsystem.org/scn/Publications/UN_Report.PDF, on June 11, 2003.

- Commission for the Nutrition Challenges of the 21st Century, Ending Malnutrition by 2020; Lindsay H. Allen and Stuart R. Gillespie, What Works? A Review of the Efficacy and Effectiveness of Nutrition Interventions(Geneva: ACC/SCN in collaboration with the Asian Development Bank, 2001); and Justin C. Konje and Oladapo A. Ladipo, “Nutrition and Obstructed Labor,” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 72, no. 1 suppl. (2000): 291S-97S.

- Micronutrient Initiative and International Nutrition Foundation (MI/INF), eds., Preventing Iron Deficiency in Women and Children: Technical Consensus on Key Issues(Boston: MI/INF, 1999).

- Lindsay H. Allen, “Anemia and Iron Deficiency: Effects on Pregnancy Outcomes,” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition71, no. 5 suppl. (2000): 1280S-84S.

- Fernando E. Viteri, “The Consequences of Iron Deficiency and Anemia in Pregnancy,” in Nutrient Regulation During Pregnancy, Lactation, and Infant Growth, ed. Lindsay Allen et al. (New York: Plenum Press, 1994): 127-40.

- Majid Ezzati et al., “Selected Major Risk Factors and Global and Regional Disease,” The Lancet360, no. 9343 (2002): 1347-60.

- Shobha Rao et al., “Intake of Micronutrient-Rich Foods in Rural Indian Mothers Is Associated With the Size of Their Babies at Birth: Pune Maternal Nutrition Study,” Journal of Nutrition131 no. 4 (2001): 1217-24; Parul Christian et al., “Vitamin A or Beta-Carotene Supplementation Reduces Symptoms of Illness in Pregnant and Lactating Nepali Women,” Journal of Nutrition 130, no. 11 (2000): 2675-82; Parul Christian et al., “Night Blindness During Pregnancy and Subsequent Mortality Among Women in Nepal: Effects of Vitamin A and Beta-Carotene Supplementation,” American Journal of Epidemiology 152, no. 6 (2000): 542-47; Keith West et al., “Double Blind, Cluster Randomized Trial of Low-Dose Supplementation With Vitamin A or Beta-Carotene on Mortality Related to Pregnancy in Nepal,” British Medical Journal 318 (Feb. 27, 1999): 570-75; and Siti Muslimatun et al., “Weekly Supplementation With Iron and Vitamin A During Pregnancy Increases Hemoglobin Concentration but Decreases Serum Ferritin Concentration in Indonesian Pregnant Women,” Journal of Nutrition 131, no. 1 (2001): 85-90.

- Siddiq Osmani and Amartya Sen, “The Hidden Penalties of Gender Inequality: Fetal Origins of Ill-Health,” Economics and Human Biology1, no. 1 (2003): 105-21.

- Saving Newborn Lives, State of the World’s Newborns(Washington, DC: Save the Children, 2001); and Jean Baker et al., The Time to Ac